Canine Distemper: Symptoms, Treatment, and Prevention Guide

Let's cut to the chase. Canine distemper is one of the worst diseases a dog can face. It's highly contagious, often fatal, and can leave survivors with lifelong disabilities. I've seen too many heartbroken owners in the clinic, clutching a lethargic puppy, wishing they'd understood the threat sooner. This isn't meant to scare you—it's meant to arm you. Because the difference between tragedy and a healthy dog often boils down to knowledge and a simple vaccine.

What You'll Find in This Guide

What Exactly Is Canine Distemper?

Canine distemper is caused by a virus closely related to the one that causes measles in humans. It attacks multiple body systems at once—respiratory, gastrointestinal, and, most devastatingly, the nervous system. There's no magic pill that kills this virus. Treatment is a brutal war of attrition, supporting the dog's body while its own immune system fights a battle it often loses.

Puppies between 3 and 6 months old are the most vulnerable, but unvaccinated dogs of any age can succumb. The American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) lists it as a core vaccine for a reason. It's everywhere.

The Sneaky Symptoms and Stages of Distemper

Distemper doesn't hit like a truck all at once. It creeps in. Many owners miss the early signs, writing them off as a simple cold. That delay can be fatal.

Think of it like this: Imagine a puppy named Max. He's 4 months old, got his first shot but missed the booster. Here’s how distemper might unfold for him.

Stage 1: The Initial Infection (Days 1-3)

Max seems a little off. Maybe he's less playful. You might notice a slight clear discharge from his eyes or nose. It's easy to ignore. Inside his body, the virus is multiplying in his lymph nodes.

Stage 2: The Systemic Assault (Days 4-10)

Now the classic signs appear. Max develops a high fever (103-106°F). The eye and nose discharge becomes thick, yellow, and gooey—like pus. He starts coughing, has trouble breathing, and loses his appetite. Diarrhea and vomiting set in. He's dehydrated and miserable. This is when most people rush to the vet, thinking it's a severe kennel cough or parvovirus.

Stage 3: The Neurological Nightmare (Weeks 3+ Onwards)

This is the game-changer. Even if Max seems to recover from the fever and gut issues, the virus may have reached his brain and spinal cord. Symptoms can include:

- Muscle twitches (myoclonus): A rhythmic jerking, often in the head or limbs. It looks like he's chewing gum constantly. This is a hallmark sign.

- Circling, head tilting, or seeming disoriented.

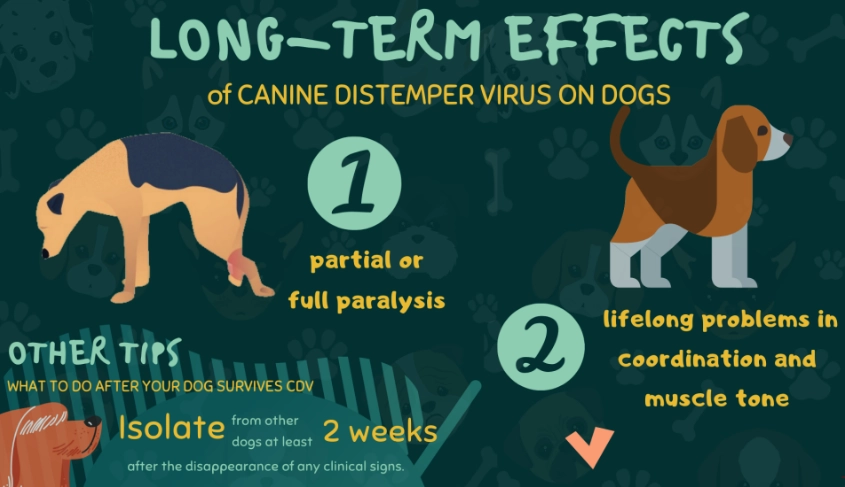

- Partial or full paralysis.

- Seizures.

Neurological damage is frequently permanent. A dog that "survives" distemper might be left with these tics or seizures for life.

How Distemper Spreads (It's Not Just Other Dogs)

This is a critical misunderstanding. You might think, "My dog doesn't go to dog parks, so we're safe." Wrong.

The virus is shed in all bodily secretions—snot, saliva, urine, feces. An infected dog can spread it through the air by coughing or sneezing (aerosol transmission). It can also be spread via shared water bowls, toys, or even on your clothes and shoes.

The Wildlife Factor: This is huge. Raccoons, foxes, skunks, and even ferrets can carry and spread canine distemper. That raccoon family in your backyard? Potential carriers. Your dog sniffing where a sick fox urinated? Direct exposure. This environmental risk makes vaccination non-negotiable, even for "backyard only" dogs.

Getting a Diagnosis and What Treatment Actually Looks Like

There's no single, perfect in-clinic test. Vets piece it together. They'll look at symptoms, vaccination history, and may run tests on blood, urine, or swabs from the eyes/nose. Sometimes, they look for viral inclusions in blood cells under a microscope.

Let's be brutally honest about treatment: There is no cure. We treat the symptoms and try to prevent secondary bacterial infections, hoping the dog's immune system can pull through.

| Treatment Goal | Common Methods Used | The Reality for the Dog & Owner |

|---|---|---|

| Fight Dehydration & Support Nutrition | Hospitalization with IV fluids. Feeding via syringe or tube if the dog won't eat. | Can be expensive. Requires days in the hospital. The dog is stressed and scared. |

| Control Secondary Infections | Broad-spectrum antibiotics (for pneumonia), eye drops. | Helps with symptoms but does nothing against the distemper virus itself. |

| Manage Neurological Symptoms | Anti-seizure medications (phenobarbital, potassium bromide), muscle relaxants. | Often a lifelong commitment if the dog survives. Quality of life becomes a constant discussion. |

| General Support | Medications to control vomiting/diarrhea, pain relief, meticulous nursing care. | Labor-intensive. Requires isolating the sick dog from other pets at home for weeks. |

The survival rate is grim. For dogs showing mild initial symptoms, it might be around 50%. Once severe neurological signs appear, that number plummets. Euthanasia is often the kindest choice when the suffering is too great, a decision no owner should have to face.

Your #1 Defense: The Distemper Vaccine Schedule

This is the happy ending. Prevention is almost 100% effective. The distemper vaccine is typically given as part of a combination shot (often called the "DHPP" or "DA2PP" vaccine).

The standard puppy series is:

- 6-8 weeks old: First dose.

- 10-12 weeks old: Booster.

- 14-16 weeks old: Final puppy booster.

- 1 year later: Another booster.

- Every 3 years thereafter: Adult boosters, as recommended by your vet.

The Booster Gap Mistake: The biggest error I see? Owners get the first shot, then think they're done. Maternal antibodies can interfere with early vaccines. Those boosters at 12 and 16 weeks are critical to ensure the puppy's own immune system is fully primed. Missing them leaves a dangerous gap in protection.

Follow your vet's schedule precisely. It's a tiny pinch for a lifetime of protection.

Your Distemper Questions Answered

My puppy survived distemper but has muscle twitches. Will this go away?

Unfortunately, neurological damage from distemper, like myoclonus (rhythmic muscle twitching), is often permanent. It's one of the most heartbreaking long-term effects. While the twitching itself isn't painful, it can be exhausting for the dog and is a constant reminder of the virus's severity. Management focuses on keeping the dog comfortable and well-rested. In some cases, medications like gabapentin might reduce the intensity, but a complete cure is rare. The presence of these 'tics' underscores why prevention through vaccination is non-negotiable.

I brought a new puppy home, and my older dog isn't fully vaccinated. What's my distemper risk?

This is a high-risk scenario I see too often. Until your older dog's vaccination series is complete and effective (usually 1-2 weeks after the final puppy shot), you must treat the new puppy as a potential carrier. Distemper virus can be shed for weeks. Strict isolation is key: separate rooms, no shared toys, bowls, or bedding, and wash your hands thoroughly between handling them. The biggest mistake is assuming a puppy from a breeder or shelter is 'clean.' Always operate under the assumption a new animal could be shedding something, regardless of source. Schedule that vet visit for your older dog immediately.

Can my dog get distemper from the park or my backyard?

Absolutely, and it's a stealthy threat. The virus doesn't survive long on surfaces in direct sunlight, but in shaded, damp areas like under bushes or in communal water bowls, it can linger. More critically, wildlife like raccoons, foxes, and skunks are common reservoirs. An infected raccoon passing through your yard can leave the virus in saliva or urine. Your dog sniffs that spot, and exposure occurs. This is why 'my dog only goes in the backyard' isn't a safe strategy. Vaccination is the only reliable shield against these environmental exposures.

Are there any home remedies that actually help a dog with distemper?

Let's be brutally honest: no home remedy cures distemper. Anyone telling you otherwise is giving dangerous advice. However, supportive care at home under veterinary guidance is crucial. Think of it as nursing, not treating. Keeping the nose and eyes clean with a warm, damp cloth helps them breathe and see. Offering highly palatable, soft food (like warmed chicken and rice) encourages eating when they're weak. Using a humidifier can ease respiratory distress. The goal is to support their body's fight, but this must always be in conjunction with professional veterinary care, including fluids and medications to prevent secondary infections.

The bottom line is stark. Canine distemper is a brutal, unforgiving disease. But it's also a preventable one. That knowledge is your power. Talk to your vet today. Check your dog's vaccine records. Don't let a simple series of shots be the thing you wish you'd done. Protect them.

The bottom line is stark. Canine distemper is a brutal, unforgiving disease. But it's also a preventable one. That knowledge is your power. Talk to your vet today. Check your dog's vaccine records. Don't let a simple series of shots be the thing you wish you'd done. Protect them.